The right place at the right time: how spending 1962 at QE broadened Mike’s education

In 1962, Mike Vanderkelen left behind the warm waters of his native Australia to spend a year in Britain’s chillier climes as a QE pupil.

It was a time of great change, both at the School and in wider British society. Timothy Edwards had succeeded veteran Headmaster E H Jenkins only the year before, and during Mike’s stay in Barnet, he experienced both the last great London smog and the dawning of the Swinging Sixties. Here, Mike records his memorable experience.

“One evening midway through 1961, my father had arrived home from his office in Melbourne with a question that would throw wide open the door to my teenage years. As my sister and I hovered around before the family sat down to the evening meal, Father asked did we want to spend a year living in England?

I don’t think I immediately understood what it might mean to live in another country – let alone go to school there – even though we were regular travellers between Melbourne and the island state of Tasmania to see my mother’s family. [Mike sent the postcard with the view of the School shown here to his grandmother in Tasmania.]

I don’t think I immediately understood what it might mean to live in another country – let alone go to school there – even though we were regular travellers between Melbourne and the island state of Tasmania to see my mother’s family. [Mike sent the postcard with the view of the School shown here to his grandmother in Tasmania.]

Previous generations of my family had been inveterate global travellers, a process that began after my Belgian great-grandfather had come out to Australia for the Great Exhibition of 1880.

But for my father, who had started his own diamond wholesaling business after the Second World War, to pack up the entire family and budget for the travelling and for a much-reduced family income must have taken some confidence and planning. His was a bold decision.

‘I would like to meet the gem suppliers I have been dealing with in Hatton Garden and see London’s diamond trade first-hand,’ he explained.

Moves across the world are now commonplace for many people, including QE alumni wanting to further their experience and their careers. In 1962, my father must have felt confident that the visit – albeit only for a year – would help grow his business.

Making the journey before international air travel had become commonplace, we disembarked at Tilbury after a five-week sea journey from Melbourne. And within days, we had received a letter from Queen Elizabeth’s inviting my enrolment at the School.

Making the journey before international air travel had become commonplace, we disembarked at Tilbury after a five-week sea journey from Melbourne. And within days, we had received a letter from Queen Elizabeth’s inviting my enrolment at the School.

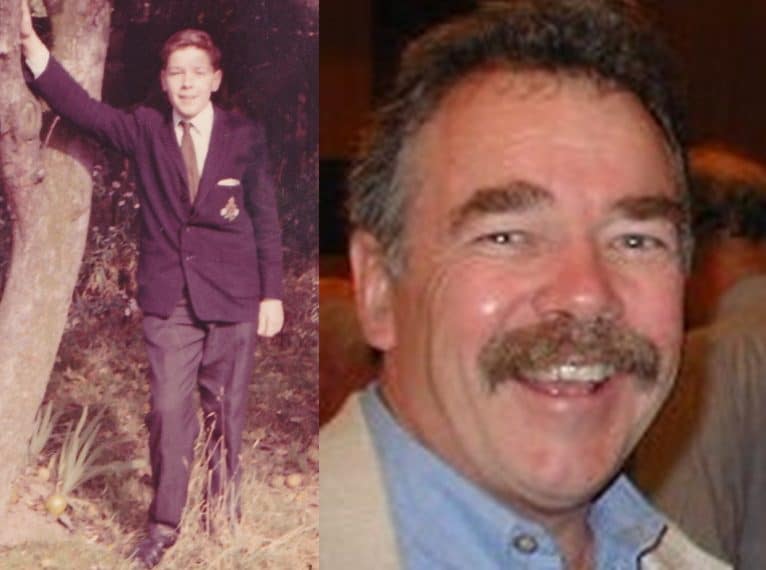

A tall and balding Timothy Edwards, who I thought then was the figure of an archetypal headmaster, accepted my enrolment for 1962. I sat silently in his offices with my parents as he briefed them on the School and its history. [Mike is pictured, top, wearing his QE blazer under an apple tree in what had been an orchard at the Manor Road house where his family lived.]

As a recent arrival in the teenager ranks, my time in England would be one of change. Its first manifestation was when I started to become conscious of the fashion statements of the time. I soon convinced a reluctant mother that a pair of jeans and a duffle coat should be part of my wardrobe.

Heading rapidly towards my 14th birthday and newly attired, I soon stepped proudly into the streets of Barnet.

At Monday morning’s classroom roll call, a balding, sports-jacketed and humorous Mr [Rex] Wingfield singled me out for special attention.

“Vanderkelen,” he said in his distinctly Home Counties accent,” I seen you down de ‘igh Street on the weeken’. Did your mum pour you into those jeans or was they painted on?” he asked, to the mirth of class.

Whether or not I responded did not matter. I had been noticed.

However, with one ‘senior’ teacher, Geography master Sam Cocks, I was noticed for the wrong reasons. I thought it a fair assumption that I should do well in a test on Australian geography – but to my horror, instead of 20 out of 20, Sam Cocks told the class I had one incorrect answer.

‘Where did I go wrong,’ I asked him? ‘Well, boy,’ he bellowed, ‘you did not correctly answer the question which asked where in Australia uranium was mined.’

My answer had been Rum Jungle in the Northern Territory, then a centre of uranium mining. But I was quickly told “no boy, that is not the answer in the book.”

If I learned a lesson, it was not one taken from the 1948 Geography textbook laid out on my desk.

If my classroom efforts at QE were mediocre, so too were my efforts at highland dancing in company with young ladies from Queen Elizabeth’s Girls’ School. Fortunately, these activities were overshadowed by some prowess in the then-open air School swimming pool and on the cricket field. With a fellow ‘colonial’, Chris Aldons from Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), we showed our hosts what warm colonial water did for one’s swimming skills. But we kept hush about any thoughts we may have had about our Ashes-like prowess.

Living in High Barnet we were closer to a more rural England than the metropolis to the south. A short distance from our flat were the lanes and hedgerows that led to the QE rugby fields and, beyond them, a horse-riding school. Equally close was Jack’s Lake in Hadley Wood. The proximity of fields for horse-riding and a lake for fishing were to foster two pastimes I would enjoy on my return to Australia.

Given my ongoing enjoyment of music and an interest in social history, I have always thought that I was in the right place at the right time in 1962. After all, I got advance notice of the musical tsunami that was about to sweep the western world with the arrival of The Beatles, The Stones, The Hollies, The Animals and a myriad of others. But during my year in Barnet, my ears and eyes were also opened to an earlier era of ‘popular’ music.

Given my ongoing enjoyment of music and an interest in social history, I have always thought that I was in the right place at the right time in 1962. After all, I got advance notice of the musical tsunami that was about to sweep the western world with the arrival of The Beatles, The Stones, The Hollies, The Animals and a myriad of others. But during my year in Barnet, my ears and eyes were also opened to an earlier era of ‘popular’ music.

It was no doubt at my parents’ recommendation that I walked up to Wood Street, Barnet, and asked for the autograph of someone whose recording career would outlast many of those who made their names in the 1960s and beyond: Dame Vera Lynn was still making the music charts well into her 90s.

As a sheepish 14-year-old kid in a black duffle coat, my photo appeared in the local paper asking for Vera’s autograph. This was one famous lady who was more than a singer. In many ways she had been idolised in Britain for her contribution to war time morale of both service personnel and the public.

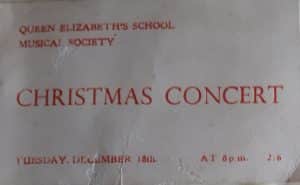

And about the same time as I was adding Ms Lynn’s autograph to my book, I was also attending the QE Christmas concert.

Just before our year in the UK was to end, the greater London area suffered its last great smog before clean air legislation and the reduction in the use of coal fires had their full effect.

A wintry outbreak brought snow to the country in mid-December. In the days before the snow began to fall and the roads to ice up, I recall seeing a yellow-ish smog seep in under the front door of our flat in Manor Road.

A wintry outbreak brought snow to the country in mid-December. In the days before the snow began to fall and the roads to ice up, I recall seeing a yellow-ish smog seep in under the front door of our flat in Manor Road.

Opening the door, I could hear the London Transport bus as its diesel engine laboured up the hill outside the house. Peering through the smog as the noise got louder, all I could see was the faint glow of the light on the upper deck as the bus passed by on its way to Barnet town centre.

Parts of southern England had heavy snow on Boxing Day. Barnet and surrounding district was in the grip of the freeze. It was indeed big news just four days before we were to embark at Tilbury for the journey home.

So almost 60 years on, I am now able to answer the question about what it would be like to live overseas and what the QE School experience did for me.

Was QE an élite institution, as several private schools in Australia aspired to be, modelling themselves on well-known English public schools? No, on reflection and despite its long history, QE appeared to be democratic and up to date, remembering, however, that this was a time when there was a real distance between pupil and teacher. It was a distance that I tried to bridge just seven years later when I spent a year teaching at a secondary school in Melbourne.

Vague whispers in the QE corridors that I had come from The Colonies were less concerning than arriving into a class half way through the School year. I was soon to find my classmates were ahead of me in several subjects.

Vague whispers in the QE corridors that I had come from The Colonies were less concerning than arriving into a class half way through the School year. I was soon to find my classmates were ahead of me in several subjects.

Since school is as much about socialising as it is about academic achievement, I began to fit in. I then continued exchanging letters (remember them?) with former classmates until the late 1960s. Our opinions about the latest releases across several musical genres were an important regular topic.

Apart from this mutual passion for music detailed in every letter, my most regular correspondent Geoff made references to the cricketing fortunes of our respective nations, wrote that the School pool would eventually be covered, that there was an Australian was on the QE staff teaching Latin and the UK was contemplating entering the Common Market.

But as tertiary studies, careers, relationships, sporting and cultural interests on either side of the world diluted our memories of QE, the exchange of letters ended.

Before we embarked for England an unnamed friend or family member – I never found out who –had recommended that my sister and I be sent to boarding schools in Australia for the year while my parents made the trip.

My father, an insightful man, said: ‘No, the experience, including school, will broaden their education.’

And, you know, I think he was right.”

- After returning to Australia Mike obtained an arts degree from Melbourne University and a commission in the Australian Artillery Reserve. In 1971 he secured a position as a journalist on the small team which launched the first business newspaper in Australia to serve the computer and information industries. This foundation paved the way for him to launch a B2B consultancy providing advice and services to global technology companies, including names such as Hewlett Packard and SAP and numerous Australasian software and hardware providers over more than 40 years. During his career he lived and worked in Melbourne, Sydney and Queensland, before returning to his home state of Victoria. Today he lives in its second biggest city, Geelong, and thinks the concept of ‘retirement’ is an onerous one, so remains busy helping build and restore wooden boats in a local community group, cultivating a large vegetable garden, enjoying food and wine (from the Geelong region’s many fine vineyards) and music. He also likes to get away to Tasmania’s central highland lakes to fly-fish for trout.